Motivation and game design

On motivation, and how it shapes human behavior and game design.

introduction

Your brain's main job is to find novel experiences. It constantly scans for surprises ~ good ones. When you get more than expected, your brain fills up with dopamine. Found €20 on the street, or received an unexpected compliment? Dopamine. It's why you keep checking your phone, why you can't stop at 'just one game', or why you do pretty much anything.

At some fundamental level, dopamine might describe all human behavior. You're reading this essay because you are looking for something valuable that exceeds your expectations. You laugh at jokes that are unexpected; explaining a joke takes away its essence because it no longer surprises you. A movie where you predict everything is boring. Perhaps after reading this essay, you will be left with something that is interesting and surprising. But don't expect too much ;-).

Dopamine is a molecule that moves across neural pathways from one neuron to another in your brain. It has a specific formula in motivating you to take action: prediction errors. Say I give you a magic button which gives you €10 from pressing it. At that moment, your brain releases dopamine. You received something valuable: money. And you weren't expecting it. A positive prediction error happened. As I continue to provide you the button, soon pressing it won't release dopamine, even though you're still receiving money. Your expectations adjusted to equal the outcome, resulting in a neutral prediction error.

If I give you the button at random intervals, you'll release dopamine not when you press the button, but when I give you the button to be pressed. Its timing was unexpected, but the outcome of pressing the button was not. After experiencing the positive prediction error once, the dopamine makes you want to experience it again. To anticipate the button. So that you could experience another positive prediction error. So you end up releasing dopamine, the wanting chemical, just from thinking about the possibility of receiving something. Which often will further motivate you to seek out the button. You don't need to have experienced it to anticipate it, just the knowledge of the possibility for unexpected positive rewards is enough.

If I instead give you the button every day a hundred days in a row and then suddenly stop, you'd probably feel pretty upset. The value was below your expectations, negative prediction error, something you actively seek to avoid. Dopamine makes us anticipate and want positive prediction errors, avoid negative prediction errors, and indifferent about neutral prediction errors. This process at its core motivates all human behavior. But we're missing the other part of the equation: how we value things.

how we value things

What we find valuable depends on our prior experiences, thoughts, psychological and physiological needs. In a way it's quite subjective. We all have different individual experiences, thoughts, desires, and preferences. Some are more universal than others. Together they shape what we all consider valuable. Many things we value are often derivatives of our core needs. We value the €10 because we value money. Money allows us to buy things, giving us control over our lives. And so it has been internalized into an inherently valuable thing. Some things, like autonomy, have inherent value though.

Remember the anticipation mentioned earlier? It can both amplify or diminish the impact of the outcome. The more we think about something, the more important it becomes. As if it begins to physically occupy more space in our brain. This evolutionary trait of anticipation serves a purpose. It motivates us to actively seek out positive experiences rather than passively wait for them to happen.

The thing with anticipation is that it will make you want something before you have it, but your expectations will end up rising too. When telling a story, never introduce it as the funniest story ever. While this might increase the audience's anticipation, it also sets difficult to meet expectations. To make them laugh you have to exceed their expectations for the 'funniest' story. So use anticipation with care.

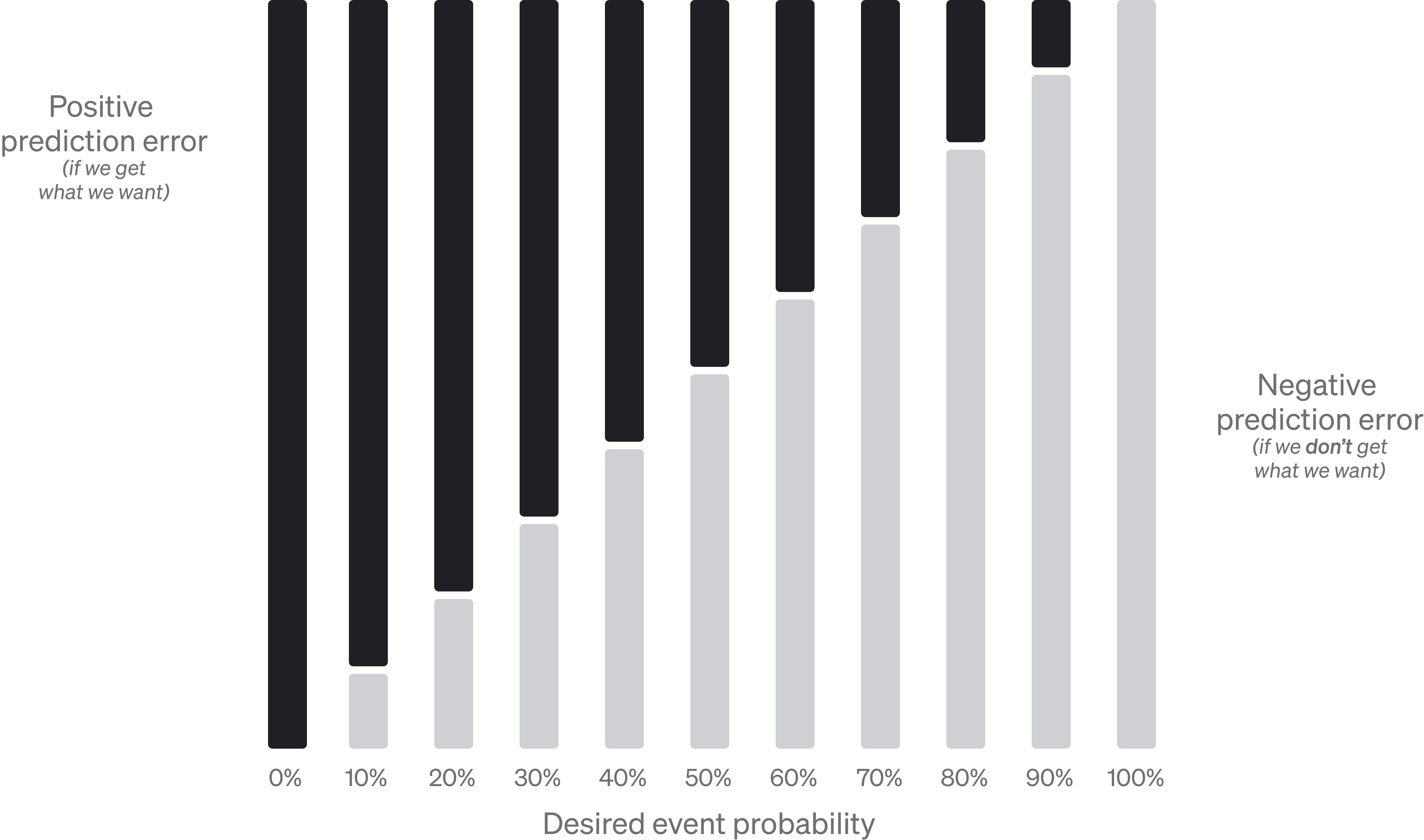

probabilities

Probabilities give shape to our prediction errors, which influence dopamine production and our motivation. Positive prediction errors trigger dopamine release, while negative ones decrease dopamine levels. Think of prediction errors as the gap between the probability for what we expect to happen and what actually happens. We can assign the outcome a value: 0% if an event doesn't occur and 100% if it does. For example, if you expect a reward with 80% chance, you'll experience a 20% positive prediction error if you get it (100% - 80%), and an 80% negative prediction error if you don't (0% - 80%). The higher the prediction error, the more powerful the effect on you.

Neutral prediction errors happen only when your expectations equal with the outcome itself. Two such cases: when you are certain something won't happen, and it doesn't happen (0% - 0%), or when something you're certain will happen does happen (100% - 100%). They don't trigger dopamine release or motivation, leaving indifferent. As we constantly adjust our expectations after each event, we create a natural drift towards neutral prediction errors. This explains why we get bored with something the more we use it. Luckily we tend to easily forget experiences. So the flow of time creates an opposing force.

For positive prediction errors, the euphoria from a 1% probability event can be quite powerful. Imagine winning the lottery. Likewise with negative prediction errors, a near guaranteed event not happening can feel painful. Imagine being told you have a deadly disease. Just the anticipation of these extreme outcomes can trigger significant dopamine release, serving as a powerful motivator.

Let's consider how prediction errors interact with how we value things. Think of the prediction error as applying a multiplier to the underlying value of an outcome. The underlying reward must still have some value potential to us. The prediction error then applies a multiplier on that value. The combination of the underlying value and the prediction error determines the overall impact of an outcome.

Take the button earlier that gives you €10 with full certainty. After you adjusted your expectations to 100%, you stopped releasing dopamine from pressing the button. The €10 is still of value to you, but the prediction error is 0. However, if the probability was reduced to 50%, you would release dopamine from each press. But if the button began to consistently give you nothing, you'd quickly adapt and stop releasing dopamine when pressing it.

Until now, I've focused on predictions error after the event. Here we only consider the prediction error and the underlying value of the outcome. Before the event, however, our motivation is shaped by a third factor: expected value. Our decisions are not purely based on prediction errors and underlying values. Otherwise, everyone would play the lottery: it has both an extremely high prediction error and reward. Instead we intuitively consider all possible outcomes known to us, both positive and negative, and weigh them by their probabilities. We're motivated to act only when this calculated expected value is high enough.

The model discussed here is a simplified representation of how our brains process probabilities and rewards. In reality, we never make such calculations with absolute precision. The numbers here don't matter much. The key insight is the relationship between expectations, probabilities and dopamine production. This underlying structure is what drives our motivation.

Our minds constantly update our expected probabilities for different outcomes in the world. Likely an evolutionary reason to make sense of our complex world, and bridge the gap between our desire for certainty, with the uncertain reality. There's something about uncertainty that works like magic in motivating us to want.

frameworks

There's no shortage of attempts at decoding human values into simple frameworks. I'll try to look at a couple of them that try to explain universal ways of what humans value.

One popular theory is the self-determination theory (SDT). It proposes three universal psychological needs:

- Autonomy: sense of control over actions we engage in

- Competence: mastery and effectiveness of actions, achieving desired outcomes

- Relatedness: feeling connected to other people

Motivation comes in two flavors: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic: we like the act. Extrinsic: we like the result of the act. Satisfying those three core needs (autonomy, competence, relatedness) boosts intrinsic motivation and well-being.

Autonomy in games is more than just freedom of choice. It's about fulfilling a fantasy we desire. This is why open-world games are so popular; you have endless ways to live out the fantasy you want.

With competence, the best games present you with a seemingly impossible challenge, then motivate you to overcome it. The cycle of struggle and mastery is motivating. Take the Souls games, one of the best in motivating through competence. The games are really difficult. You'll die at least 500 times during your playthrough, 1000 if you suck at the game. But somehow they've managed to bake dying as part of the core experience. So eventually defeating that super difficult boss feels incredibly satisfying.

And with relatedness there's something in our monkey brains that creates satisfaction for connecting with others and belonging to a group. Probably because it used to be mandatory for our ancestors' survival.

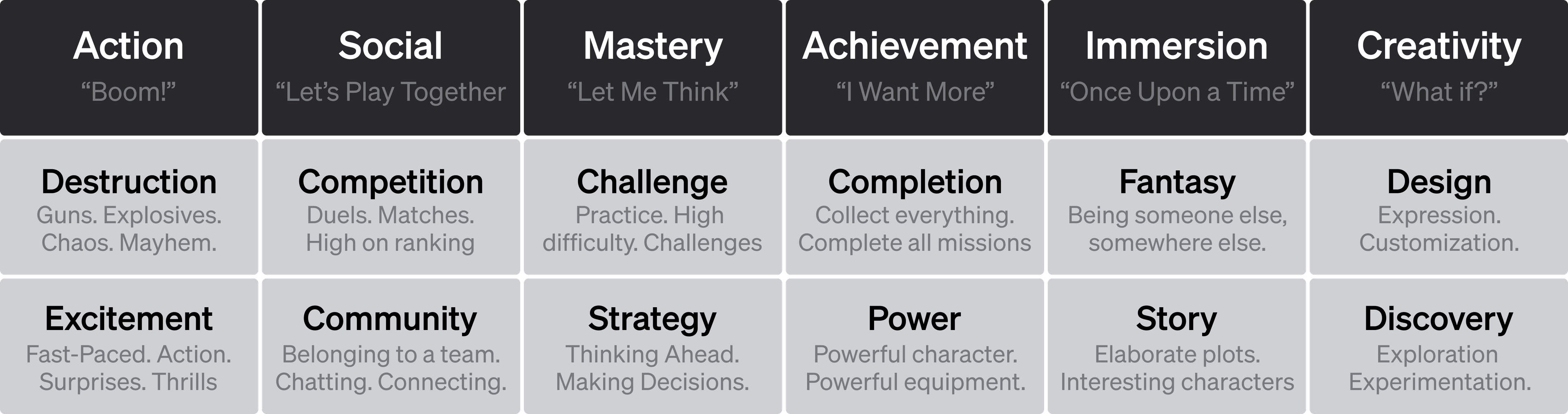

Quantic Foundry's framework on the other hand focuses specifically on game design motivations.

The model groups gaming motivations across 12 different spectrums. While SDT addresses universal human needs, this targets specific gamer motivations, a smaller demographic. Every game fulfils some combination of the motivations. It maps quite well the existing and somewhat universal motivations for playing games. But people change. So do their desires. In 100 years that list might look very different. I fear that too many risk-averse games only try to serve the needs of existing gamers, instead of new audiences.

Genres themselves serve as a framework for understanding player motivations. Unlike the previous frameworks, genres don't describe inherent needs. They represent the bridge between player motivations and what the industry has created to serve these motivations. Players use them as a shorthand to determine various forms of value potential from a game.

It's easy to recognize and enjoy a great game when you are playing it. Accurately predicting your enjoyment from a specific game beforehand is the hard part. Time and money is limited, so you end up going for the games you already know to generate great experiences. We end up categorizing games in our minds. When someone expresses their genre preference, they're really talking about their experiences. Saying 'I don't like that genre' often means 'that genre hasn't previously generated positive prediction errors'.

While useful, genre lock-in can lead to narrow experiences that only serve a small portion of motivations. Depriving players of all the various new games they could gain immense joy out of. The best games succeed in going beyond this genre lock-in. Offering universal appeal, they satisfy a broader range of player motivations than typical genre-specific games. Think of games like Minecraft or GTA V.

Ultimately the frameworks ~ SDT, Quantic Foundry's model, and even genres ~ are attempts to understand how humans value different gaming experiences, all underpinned by the dopamine-driven anticipation of a reward.

Frameworks help, but fail to capture the full complexity of human desire. What matters more is the collective experiences of all humans, and specifically your target audience. How these have shaped their expectations, and motivation to seek out specific experiences. The hard part is making something that appeals to a massive and diverse audience. Looking at genres or frameworks will only limit your sights. Better to look towards crafting great experiences that resonate with as many as possible, as strongly as possible.

player journey

How does dopamine shape game design for each of the core steps of a player's journey in a game?

- Acquisition: downloading the game for the first time

- Engagement: player experience inside the game

- Resilience: leaving and returning to the game

All games try to optimize these core steps of the player journey. But, the design for each step looks a lot different for a free-to-play mobile game than it does for an upfront price premium game.

acquisition

Companies are willing to spend millions in marketing just to get players into their free-to-play games. The goal is to create the possibility of positive experiences in the minds of your audience. The only way they will download your game is if they believe that they can receive positive prediction errors from playing it. So you need to first occupy their mindspaces, and then promise them value that will exceed their expectations. Enough to anticipate and want the game before even experiencing it.

Promise too little and nobody will play your game. Promise too much and you'll be left with a tarnished brand. No Man's Sky took the latter route and received one of the worst backlashes in gaming. They promised the universe, but only delivered a couple boring identical spheres. On purpose or not, the player expectations were so high that No Man's Sky had no chance of exceeding them. Becoming one of the largest flops in gaming. But ultimately they managed to redeem themselves. Each year they would release, and still do, a content expansion after another. Nobody expected it from them. In fact, the expectations were rock-bottom after the initial launch. This gave them a chance to redeem themselves by exceeding player expectations and delivering value.

The balance is to promise enough to make them download the game, but not too much to still exceed their expectations when they play the game. You want them to have positive surprises while playing the game too. The hurdle is different depending on how you make your money. It's easier to acquire a player into a free-to-play game than into a game with an upfront price. But this also impacts their commitment with the game and resilience, which we will get to in a moment.

engagement

After someone downloads a game, the next step is to make sure they actually receive those positive prediction errors. Now, they've arrived with a specific set of expectations based on what they were promised, and everything else they associate with the game. The genre, the developer, similar games, and everything remotely familiar. All of which impacts what positive prediction errors they might experience.

Give them enough positive prediction errors to keep them engaged and want more. But not too much to avoid depleting future possibilities of positive prediction errors. The goal is not to give them a single amazing session, rather to make sure they keep coming back for the lifetime of the game, be it a few months or forever. This requires a constant source of positive prediction errors and the possibility of receiving them in the future too. This is hard because expectations adjust quickly. Similarly what you value changes over a longer time horizon. You value different things when you are 10 vs. 15 vs. 25 years old .

Different games approach engagement differently. Competitive multiplayer games like League of Legends, Counter Strike, Overwatch and Fortnite engage you the through diversity of players' playstyles and the unpredictability of the outcome of the match. The opponent pool is often in the millions, and the competitive matchmaking model always puts you in a game with players of similar skill level. The better you are, the tougher the opponents. So your winning probability will often hover around 50%. If you value winning the most, your expectations will never adjust. This creates a constant source dopamine from winning, as well as anticipating it.

Singleplayer games with campaigns are shortlived, but for a reason. Your expectations adjust quickly and are surpassed only after experiencing something for the first time. Despite experiencing a beautiful world, you are no longer motivated to experience it again. But if your main goal is not to retain your audience for as long as possible, but rather give them a memorable experience, then this model works just fine. After all, these games don't make their money on keeping players for as long as possible, but to ensure their experience is great enough to share this knowledge with others that might buy it.

Some games try to solve this problem through using loot boxes — a lottery-like reward system. Their design closely mimics gambling though. In Brawl Stars you have Starr Drops that give varying rewards based on different probabilities. The outcomes are always random, which ensures that your expectations never fully adjust. The dopamine release is layered into two parts. The first dopamine release happens from tapping your screen, which determines the rarity of the reward. And the second dopamine release comes from unlocking the reward itself. A simple progression mechanic is now an exciting dopamine-driven experience.

Uncertainty can help increase your audience motivation, but it needs to be combined with something that actually creates value for the players' needs. It is only a multiplier after all. With Brawl Stars you receive progression rewards that help you advance in the game. The probabilities should always be above 0% and below 100% to ensure the possibility of prediction errors. The exact number, however, depends on the perceived value of a specific outcome, and player resilience.

resilience

Resilience is the part that makes your audience return to your game after leaving it. They'll return so long their desire for positive prediction errors exceeds their threshold to act. This threshold is defined by commitment to a game. And their desires are influenced by what they experienced while playing the game.

At some point eventually your audience will leave your game. The worst possible reason is one that decreases their anticipation for positive experiences in the future. Overpromising and underdelivering might leave them feeling that the game cannot give them positive prediction errors. Ideally the first moments are designed to ensure that the players keep wanting that dopamine from the game and return to it.

The initial commitment in free-to-play mobile games is so low that the first moments can make or break whether a player ever returns to the game. Mobile games solve this issue by providing endless positive prediction errors while avoiding any negative ones. Competitive games initially match you against bots to ensure you win. And well-crafted tutorials ensure you learn all the necessary basic details. You're given positive experiences to get a taste of the dopamine and build your commitment towards the game.

Commitment is the part that determines the threshold of positive prediction errors required to return to a game or download it in the first place. Paying €70 upfront for a PC game builds more commitment than downloading a mobile game for free. With free mobile games, the slightest negative experience might make you instantly delete the game and never return again. You haven't mentally committed to playing the game yet. But with the €70 you already paid the story is different. You're willing to endure more negative prediction errors and be more patient in your search for dopamine.

But free-to-play games have a trick up their sleeves. If you don't drop out within the first moments, you might just end up playing the game for years. And you'll be a lot more committed to continue after playing for several years.

There are different design choices to tackle resilience. Competitive games often have extreme highs and lows due to outcome probabilities, and how all the value is loaded into the outcome of a match. Too many losses will make you quit the game for good. Some competitive games like Squad Busters, Fortnite, Brawl Stars use bots, so you'll receive more positive prediction errors from winning. People on average think of themselves as better than average: winning only 50% of the time will feel bad. But the challenge with bots is that they reduce the value of the positive prediction errors. It's not fun winning against them, because it doesn't feel like playing against other humans.

FromSoftware's games such as Elden Ring or the Souls series approach this by modifying player expectations. The games are played with the clear expectation that you will die hundreds, if not thousands of times. So you'll keep playing despite dying again and again. This becomes a powerful motivator when combined with your desire for competence and mastery.

A simpler way to improve resilience is to create more content. Events, season passes, DLCs, new levels and so on. They all promise players new positive experiences they could gain from the game. The problem with these is that they don't scale very well. Player expectations adjust relatively quickly, and the required amount to exceed expectations keeps on increasing.

implications

Everything we experience is relative to our own internal expectations. We can shape these expectations with attention alone. Just try it out for yourself and see how easily you can change how you experience an event. Be careful though, extreme pessimism might ensure that you'll experience less negative experiences. But A. nobody will like you and B. you'll rarely seek out new experiences and take risks on things that could give you more positive experiences. Extreme optimism on the other hand might make you move mountains, but you'll feel the negative prediction errors a lot more. Which bucket do you think the greatest builders of our time fall into?

Similarly you can design the attention of others. Our universe is formed by how we experience it. So we shape our own universe with just our attention, and the universe of others through designing their attention.

You have the universe, now what will you do with it?

-

Could it also be the only task it has? Everything else being a derivative of it?

-

'Prediction error' sounds so formal, but really just describes unexpectedness; how far off you are from what you predicted.

-

See also Bartle's Taxonomy and Reiss Motivation Profile.

-

Specifically with intrinsic motivation the action itself generates positive prediction errors. And with extrinsic motivation the outcome of the action generates positive prediction errors.

-

FromSoftware integrated this so well into their games, they ended up popularizing a new subgenre, Soulslike games.